Participants

Information about the authors of the text and music, as well as on the performers and the scenes, is given in the overviews in the printed libretto and in the score copies.

In addition to Conti and Pariati, Giuseppe und Antonio Galli Bibiena are also mentioned; they created the stage sets and scenery in their well-established manner. Alessandro (Alexandre) Phillebois is listed as the court dance master responsible for the balletti. responsible for the balletti. Four dances – named as “Aria” in the sources – are intended for Penelope; it was intended that they should be performed at the end of the opera, after the chorus. Usually, these dances were not written by the composer of the opera, but by the director of instrumental music (in this case, Nicola Matteis d. J.) or by the ballet composer (in this case, Phillebois). In the sources for Penelope, the composer of the balletti is not explicitly mentioned; the note “Il Ballo fu vagamente concertato dal Sig. Alessandro Philebois” or in the German translation „Der Tantz ist von dem Herrn Alexandro Phillebois, der Röm. Kaiserl. und Königl. Cathol. Majestät Tantz=Meistern auf das kunstreicheste angeordnet worden.“ can be understood to indicate that Phillebois choreographed the dances, but not necessarily that he wrote them. As with other carnival operas, Matteis probably also contributed the music to the dances of Penelope.

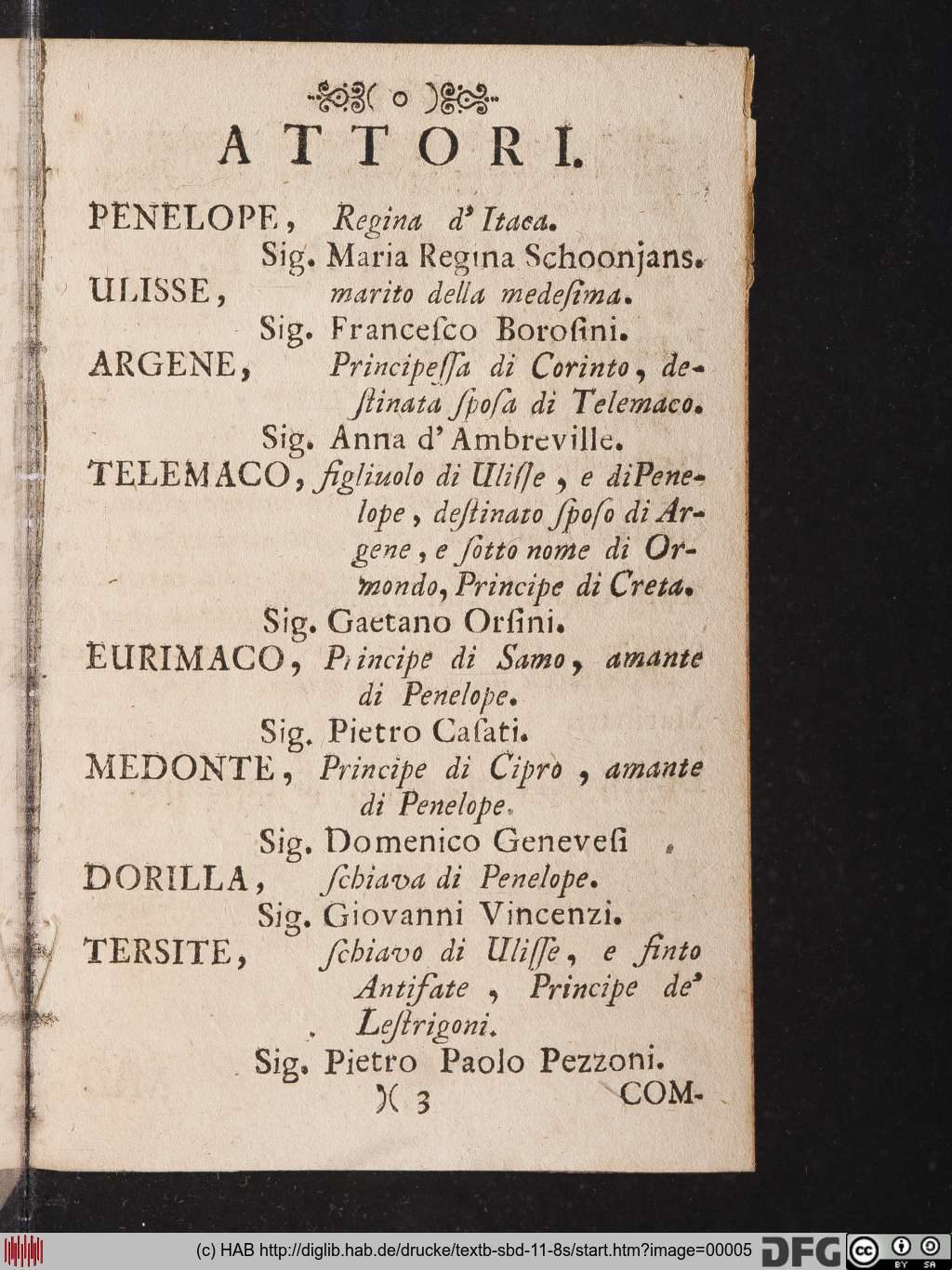

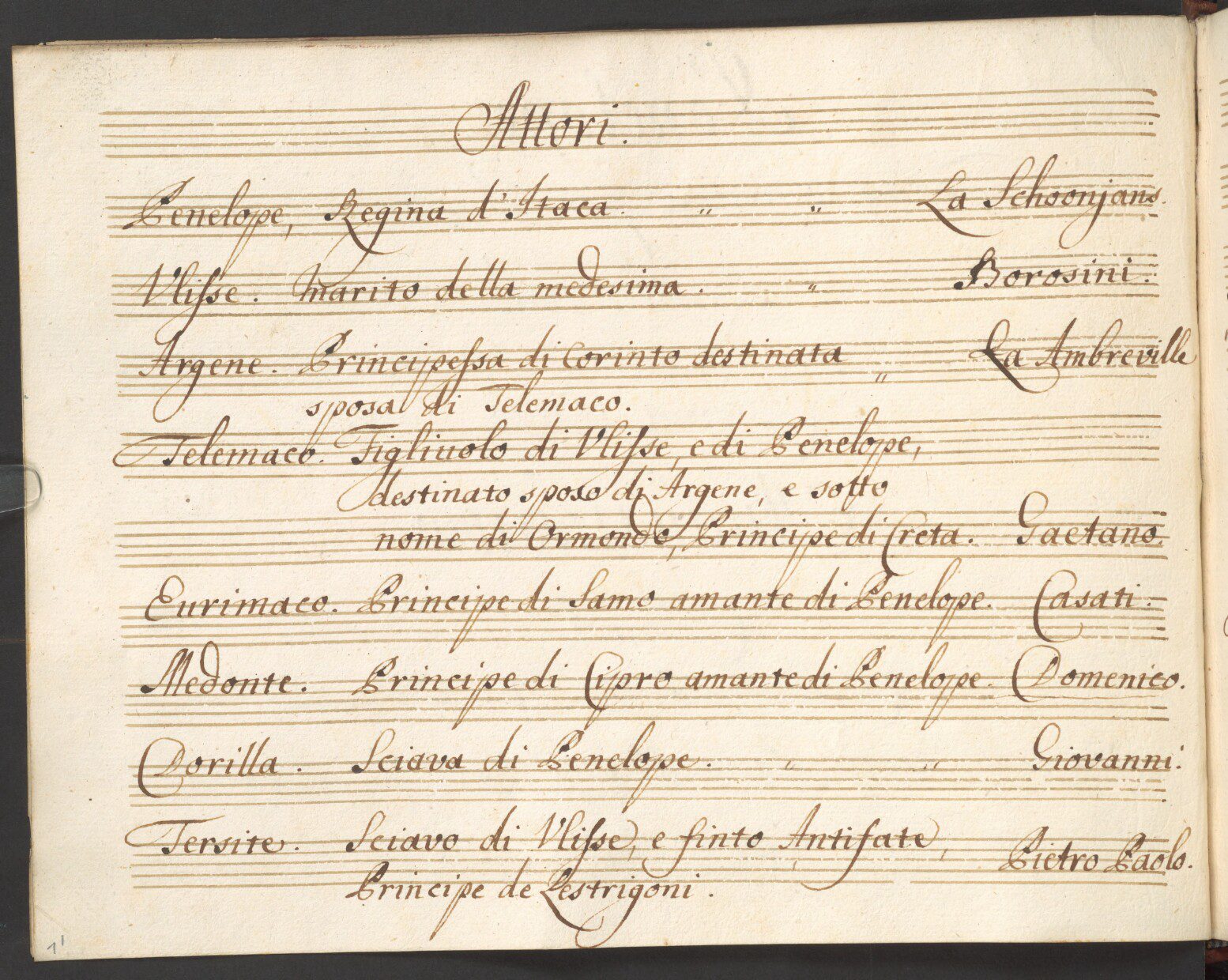

The names of the singers from 1724 have been preserved thanks to the precise records in the libretto and the score; all of the singers were employed by the court and the roles were tailored to their singing and acting abilities.

The title role of Penelope was sung by Regina Schoonjans (née Schweyzer, ca. 1766-1759), a soprano at the Viennese court who, from 1714, was much in demand for prominent roles in numerous musico-dramatic works by Conti, Fux and Caldara. In 1713/14 she was still singing without a salary, but in 1717 she was employed and became one of the best-paid singers at court. Until 1722, Conti's wife Maria Conti-Landini was the prima donna who sang the leading roles; after her death, Regina Schoonjans took over this function until 1725, when Conti’s second wife, Anna-Maria Lorenzoni-Conti, once again relegated her to the second position.

Ulisse, Penelope's husband, was sung by the tenor Francesco Borosini (Modena c. 1690 – between 1741/61), performed full-length operas, especially comedies, despite an imperial interdiction. As a singer, Borosini was characterized by outstanding technical skills and a wide vocal range (F-b'). He regularly played the leading male role in Viennese carnival operas. In addition to his musical skills, he also possessed great acting talent and stage presence, enabling him to portray a great variety of characters. In 1719, he asked the court conductor Fux for an increase in salary, which was granted, as Borosini was “a very good virtuoso; and in theatrical matters he is peculiarly distinguished [...]”. (da er „ein sehr guter Virtuos ist; Vnd in Theatralsachen sich sonderbar distinguiret […]“; Ludwig Ritter von Köchel, Johann Josef Fux. Hofkompositor und Hofkapellmeister der Kaiser Leopold I., Josef I., und Karl VI. von 1698–1740, Vienna 1872, p. 385).

Anna d’Ambreville, sung the role of Argene. She was the sister of Rosina (Rosa) d'Ambreville, who in turn was married to Antonio Borosini. Both sisters were singers at the Viennese court and took part in the performance of Johann Joseph Fux's Prague coronation opera Costanza e fortezza in 1723.

Gaetano Orsini (c. 1667–1750), Telemaco, was an internationally famous and admired alto castrato who was part of the imperial court chapel from 1698 and sang important roles in many court operas. Johann Joachim Quantz praised Orsini’s pure intonation, his trills and his tasteful performance in both fast and slow arias, with which he sang his way into the hearts of the audience. He is also praised in Pier Francesco Tosi’s singing instruction. He kept his voice well into old age.

Eurimaco, the second alto role in the opera, was sung by another castrato, Pietro Casati (Casato; 1684–1754). Casati, who also composed, was in the service of the Viennese court chapel from 1717 until his death and received a high annual salary of 1800 guilders. He took part in numerous carnival operas.

The soprano castrato Domenico Genovesi (Genuesi, dates unknown) sang the part of Medonte. Not much is known about his life; he was a member of the Vienna court chapel from 1717 or 1718 until his retirement in 1752 and received an annual salary of 1440 florins. Like many of his colleagues, he also took part in the Prague performance of Costanza e fortezza in 1723, where J. J. Quantz probably heard him. Quantz praised his penetrating and pure soprano voice, but criticized his not very lively playing.

The comical role of the servant Dorilla was played by Giovanni Vincenzi (1698–1739), soprano castrato. In 1713 he joined the Viennese court chapel, in 1727 he was promoted to first soprano and received an annual salary of 1440 florins. Vincenzi also appeared in other carnival operas, often in comical female roles.

The servant Tersite was sung by the basso buffo Pietro Paolo Pezzoni (1667–1736), who joined the Viennese court chapel in 1715 and was active until his death in 1736, specializing in comic roles. At 1260 florins, he earned less than his colleagues, with whom he sang in Penelope; however, he must have had considerable acting talent to convincingly portray the buffo roles in the intermezzi and carnival operas, and especially the role of Tersite.

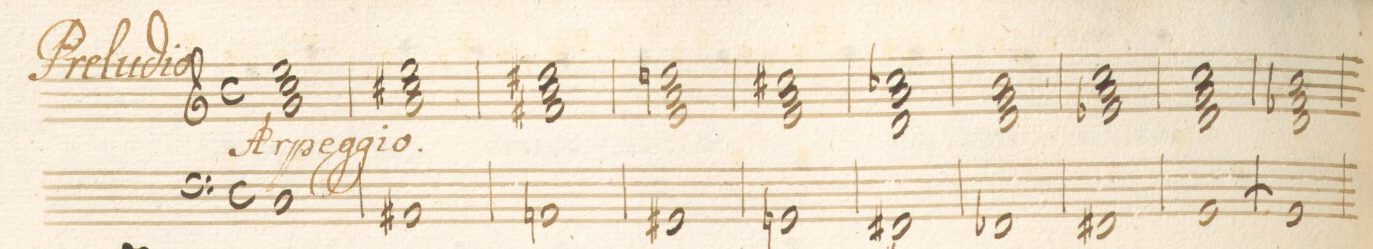

A-Wn Mus.Hs. 17226/2

The orchestra was made up of members of the court orchestra. Conti may have played the theorbo in the continuo group. Penelope contains no virtuoso instrumental solos, with the exception of the salterio part in the aria of Tersite (no. 29) in Act II. Maximilian Joseph Hellmann (1702/3–1763) was a timpanist and dulcimer virtuoso at the Viennese court, playing a large, precious instrument with 185 strings, which was called the “Pantalon” after its inventor Pantaleon Hebenstreit. Hellmann was sent to the Dresden court in 1719, where he was personally trained by Hebenstreit. At 1,000 florins a year, he earned very well for an instrumentalist, but was constantly in financial difficulties due to the high maintenance costs for his instrument and asked for a pay rise, which the court conductor Fux granted; however, Fux also recommended that the musically outstanding, but financially less skillful virtuoso be given a curator so that “his evil dignity could be remedied”. („seiner üblen würthschaft vorgebogen werden“ soll; Köchel, Johann Josef Fux, p. 406)