Francesco Bartolomeo Conti

Francesco Bartolomeo Conti (20.1.1681 or 1682 Florence – 29.7.1732 Vienna) came from an Italian family of musicians. He married two court singers in his second and third marriages: Maria Landini and Maria Anna Lorenzani, who also performed in his own operas. His son Ignazio Maria, from his first marriage to Therese Kugler von Edelfeld, was also a composer and musician.

Report of Conti's marriage in Wienerisches Diarium no. 226, 3.10.1705 [p. 9]

Ignazio Maria was also a source of some grief to his father, because due to a misidentification, Francesco Bartolomeo Conti had the dubious pleasure of being the subject of a scathing article by music critic Johann Mattheson, who described him in his book Der Vollkommene Capellmeister (Hamburg 1739) as a “great, unfortunate musician with great moral weakness.” According to Mattheson, Conti had been involved in several fights in Vienna, notably with clergymen. For these “tangible arguments,” Conti was sentenced to four years in prison, ordered to pay 1,000 guilders in damages, and to cover the costs of the proceedings, and he was also expelled from the country.

Mattheson embellishes his report with a whimsical epigram that addresses Conti's compositional style, which did not quite conform to the rules of good taste:

Johann Mattheson, Der Vollkommene Capellmeister, 6. Capitel, § 48 ("Auszug eines Briefes aus Regensburg, vom 19. Oct. 1730"), p. 40f.

"This muse is not good, nor is the music you have composed,

Conti, for every bar was ponderous:

And the bass too coarse, even the final note is not consonant:

From now on, you will carry black notes [blemishes] within you forever."

(based on a translation into German by Alexander Rausch, Vienna)

However, Francesco Bartolomeo Conti's biography shows that he was employed at the Viennese court until the end of his life – unlike his congenial colleague Pariati, who also had a prison episodeon his record, Conti was innocent. As early as 1755, his reputation was publicly restored when Johann Joachim Quantz made it clear in Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg's Historisch=Kritische[n] Beyträge[n] zur Aufnahme der Tonkunst (Vol. 1, 1755, pp. 216–220, note on p. 219) that the unfortunate man in question was Conti's son Ignazio Maria, who was also a composer. Nevertheless, as Mattheson had predicted, this defamation persisted even into the 20th century.

Conti was one of the many Italian musicians who influenced the musical life of the Viennese imperial court in the 17th and 18th centuries. He served the Viennese court for around 30 years between his first appointment in 1701 and his death in 1732, serving three emperors, Leopold I, Joseph I and Charles VI. His outstanding compositional skills and general musicianship allowed him to be retained during the critical years of 1705 and 1711, when the court chapel was dissolved and reorganized and reduced due to the death of the rulers; in 1711, during an evaluation of the musicians, the chapel masters Ziani and Fux unanimously voted for him to remain in the court chapel.

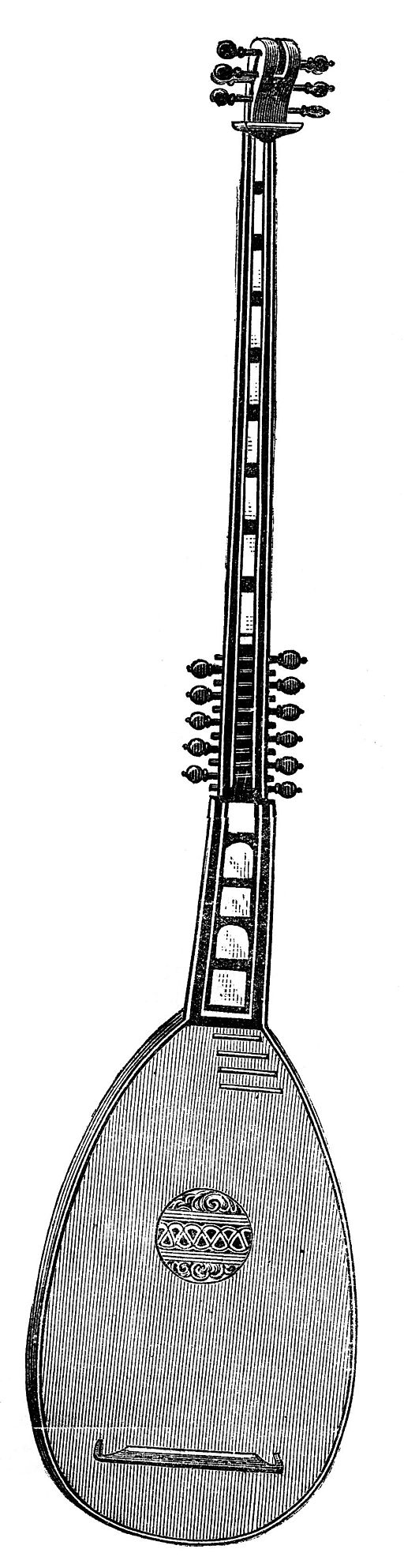

Conti was primarily known as a virtuoso on the theorbo, a large lute instrument with bass strings. In 1701, Emperor Leopold I called him to the Viennese court as theorbo player, where he performed both as a soloist and as a member of the continuo group. Whilst he was in Vienna, Conti also composed, although he was not under any professional obligation to do so.; that he was as highly regarded as a composer as he was as an instrumentalist is shown by performances of his own works in London in 1707 before the Queen, and in 1713 he was promoted to the position of imperial court composer. In 1725, not long after his third marriage, Conti fell ill and was unable to play his instrument or compose; no new music was composed by him for the Viennese court between 1727 and 1731. How rare good theorbists were and what a huge gap Conti's absence meant can be seen in the difficulties that the chapel master Johann Joseph Fux had in finding a replacement for Conti – Joachim Sarao, who had been hoping for a permanent position for some time, was hired, but to his disappointment on much worse conditions than Conti.

Theorbo, c. 1580, Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:377-Italian-Lute,-about-1580-q75-867x3361.jpg)

In 1732, Conti composed his last work, the oratorio L’osservanza della divina legge. His will is dated mid-July of the same year; he died in Vienna on July 20. Conti is listed among the deceased “in the city” for July 20:

Wienerisches Diarium Nr. 59 vom 23.7.1732 [S. 7]

Although Conti himself was an instrumentalist, only a few of his instrumental works are known and preserved. At the Viennese court he composed much vocal chamber music, both sacred and secular (cantatas, serenades), as well as works for larger forces, such as oratorios and operas, which he composed for liturgical and dynastic occasions. Conti had a particular talent for the comic genre; between 1714 and 1732 he was commissioned twelve times to compose a large opera for the carnival at the Viennese court – one of these was the Tragicommedia per Musica Penelope, which premiered in 1724.

Conti’s operas were less exclusive to the Viennese court than, for example, the operas of court conductor Fux: they were copied many times and performed in cities and courts such as Hamburg, Dresden, Breslau, Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, Brussels, Prague, Brno, Jaroměřice and even London – Ormisda was specially arranged by Handel for this purpose. For reasons that are no longer known, however, Penelope remained a purely Viennese production.

Literature

Francesco Bussi, Angela Romagnoli, Art. "Conti (I)", in: MGG Online, ed. Laurenz Lütteken, New York / Kassel / Stuttgart 2016ff., first published 2000, online published 2016, https://www.mgg-online.com/mgg/stable/13435

Herbert Seifert, "Conti und Pariati – ein Glücksfall für die Operngeschichte", in: Innsbrucker Festwochen 12. Juli – 27. August 2005, Innsbruck 2005, S. 28–33, reprint in: ibid., Texte zur Musikdramatik im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert: Aufsätze und Vorträge, ed. Matthias Pernersdorfer (Summa summarum 2), Wien: Hollitzer, 2014, pp. 559–562.

Hermine Weigel Williams, Francesco Bartolomeo Conti. His Life and Music, Aldershot: Ashgate1999.